Why Is *THAT* A Musical?

/If I had a nickel for every time I was asked this question, or even asked this question myself, I would have a very large number of relatively heavy and annoying coins.

But I do wonder - How often do people hear about a new musical or see a marquee and think this question to themselves? I mean, what makes a story ripe for adaptation into a musical? Why do some musicals seem like no-brainers, while others make us scratch our heads and think, “Huh. Really? That one?”

The Lehman Engel BMI Musical Theatre Writing Workshop answer to the question of what type of stories should be adapted into musicals is a relatively simple and subjective one: If you think there’s more within the story that should be told, and that music will enhance that storytelling, then it is likely adaptable into a musical. But if the story feels complete in its current form, and it doesn’t seem like music will enhance the piece and its purpose, it should probably be left alone.

Despite the subjective nature of this statement, I do think there’s truth to it. If you look at the types of stories that have been most successfully adapted into musicals (and most musicals are adaptations), the use of music in the storytelling has heightened the plots and characters, and filled in some invisible hole that helps the audience interact with the material.

This is the reason, I think, that certain stories see multiple attempts at musical adaptation. For a couple of examples, we have 2 adaptations of The Phantom of the Opera, 2 musicals of The Wild Party, and countless musical versions of Shakespeare’s plays (most of which have not worked well). Some stories feel as though they could be told well, or better, in musical theatre form and therefore multiple adaptations appear. Some are good, and some aren’t. Some use the original author’s intents, and some leave them behind.

Successful adaptation is a tricky process - and I know this from adapting one of the most-adapted stories in musical theatre, The Legend Of Sleepy Hollow. Approximately 5-6 musical versions of this story exist, but none of them has had great mainstream or commercial success. Yet. But why? What goes into this process?

Logo for the Bristol Valley Theater reading, October 2018

“Adapt or Perish”

Thanks H.G. Wells! In the natural world, I totally agree. But in the theatrical world, I would probably alter it to say: “Adapt well or perish.”

Adapting a story for the stage is difficult, especially when it’s well-known. Adapting a story into a musical specifically adds many additional layers of difficulty.

But Michael, wouldn’t coming up with an entirely original story be harder?

Why yes, sole reader of this blog! In many ways an original musical is much harder, since the entire burden of plot and character rests on the writers. There’s nothing to build from.

So then, what’s the issue?

Excellent question!

There are 3 main issues I see when it comes to making a musical adaptation:

Audiences enter with ideas about the story and characters already formulated.

The original author’s intent and basic structures may or may not still be present.

Music is meant to enhance, but what exactly are you enhancing for your version?

Audience Expectation

When adapting a well-known story, book, movie, play, etc., your audience will come into the performances with preconceived notions.

Now, perhaps they’ve never actually encountered the original material, but that doesn’t mean there won’t be an image, idea, feeling, emotion, or otherwise already planted, which will color their expectations. So how does this alter your approach?

In all honesty, I wouldn’t give it too much thought.

What?! But if your audience isn’t on board, then you’re sunk!

True. But the best way to get the audience on board with what you’re writing is simply to write well. The only real decision you have to make is whether you’re going to take the story in a direction that will feed into audience expectation, or break from it (and to what degree). But, if you successfully create and introduce your world and characters to the audience and set them up for the journey you’re going to take them on, then they will follow.

Application: The Legend of Sleepy Hollow

One of the most interesting things my composer and I have encountered in adapting The Legend of Sleepy Hollow has been the complete and utter variance in the levels of familiarity with this story.

I can say that title to anyone and some sort of preconceived notion will suddenly appear, but it is vastly different depending on the person. Some people have only ever seen the Disney short film. Others the Tim Burton film. Others had a watered down version read to them as a child, but don’t remember anything about it. Some people have no idea what you’re talking about until you say the words “Headless Horseman.” New Yorkers read this story in school, but basically no one else in the country does. And almost no one has read the story recently or has a particularly accurate idea of what takes place in its small number of pages.

Quite the range, eh?

So what did we learn from this?

We could never in a million years satisfy everyone’s expectations, so we shouldn’t try.

The name of the story is evocative in and of itself.

General feelings about the story seem more pervasive than the actual characters and plot.

Only certain images are universally retained, namely that of the Headless Horseman.

Author’s Intent

What is this story about? Why was it originally told? Why should it continue to be told? What did the original author want their audiences to take away? What do you want your audiences to take away? Are they the same?

Far too often I see musical adaptations that have abandoned the original intents and message of the story. Suddenly, an entire plot point will disappear, or a character will make a decision that’s inconsistent with the plot. Is it okay to do this? Certainly! However, the most successful adaptations that make these changes tend to abandon the brand of the original story, treat the original more like a guideline, and come into their own as an individual piece of musical theatre.

Small example: we all know that West Side Story is essentially Romeo and Juliet, but it also isn’t. The basic plot is still there, but characters are added and subtracted as needed. Tony and Romeo are not very alike if you compare them side by side. The purposeful movement of the time and setting add and subtract layers from the story. And the biggest change: the entire ending sequence. Romeo and Juliet is famous for its graveyard scene, whereas in West Side Story the sequence of events has been altered and Maria is left to live with the results. But has Shakespeare’s message been lost? I personally do not think so.

Now, I’m not saying that to keep a title or a brand you must strictly adhere to the original author’s structure, plot, and character creation. You have chosen this piece to enhance it, which will require changes. But if a piece was written to highlight social injustice and you alter it so much that this message becomes completely lost, then you may need to rethink your adaptation. Or if a character is famous for being one way because that drives the story, but you subvert that, then the piece just might crumble.

Application: The Legend of Sleepy Hollow

This was a tricky one. We spent a great deal of time trying to determine what Washington Irving’s purpose was in telling this story.

Was it a commentary on social constructs and collective thinking? Was it about superstition and its effects on a community? Was it a cautionary tale about individual gullibility? A comment on small-town American life? A slight aimed at Dutch settlers and their descendants? A celebration of the haunted nature of the beautiful American landscape? A questioning of what is real? Or was it just a silly little tale?

The key for us was when we remembered that this story, which has only a handful of spoken lines, was not actually being told by Washington Irving. In the collection of tales, there is a narrator who provides us with the context for the story of Ichabod Crane, Brom Bones, Katrina Van Tassel, and the Headless Horseman, and then he gives us the story itself. It was a story within a story.

So why was the narrator telling us this story?

The answer to that question ultimately did not matter, for we had found our way in. Stories are told with purpose, whether or not their contents are true. And this was the common thread throughout The Legend of Sleepy Hollow.

Storytelling cropped up throughout the piece, in the form of ghost stories, minor tales of the countryside, re-tellings of American Revolution battles, and lots of town gossip. All of this while being narrated by a character who has his own reasons, but who is also being written by Washington Irving. And this was the point of the piece: Why do we tell stories, and how do they help us get what we desire?

Music and Story Enhancement

Music is evocative. Music is language. Music is math. Music is emotion. Music is ethereal. Music is nebulous. Music can have an immeasurable impact.

So why a musical? How is music going to help you tell this story? Why is music the thing that was lacking from the original story, and how will you utilize it to strengthen the piece? Why are they singing?

There are a million-and-one ways to answer these questions, but here’s the key: You had better have an answer and it better be a good one. And additionally, the audience better be able to pick up on your reasoning, consciously or unconsciously.

Some people self-proclaim that they hate musicals, and the reason they give is generally the same: Why are they bursting out into song? It doesn’t make sense. People don’t do that.

***Side Note: Anyone who says this clearly doesn’t spend enough time around musical theatre folk.

The incorporation of music has to be earned. The circumstances or emotion must be so great, so heightened, that music not only feels natural at that moment, but necessary.

This is so incredibly important, and I cannot stress it enough.

Application: The Legend of Sleepy Hollow

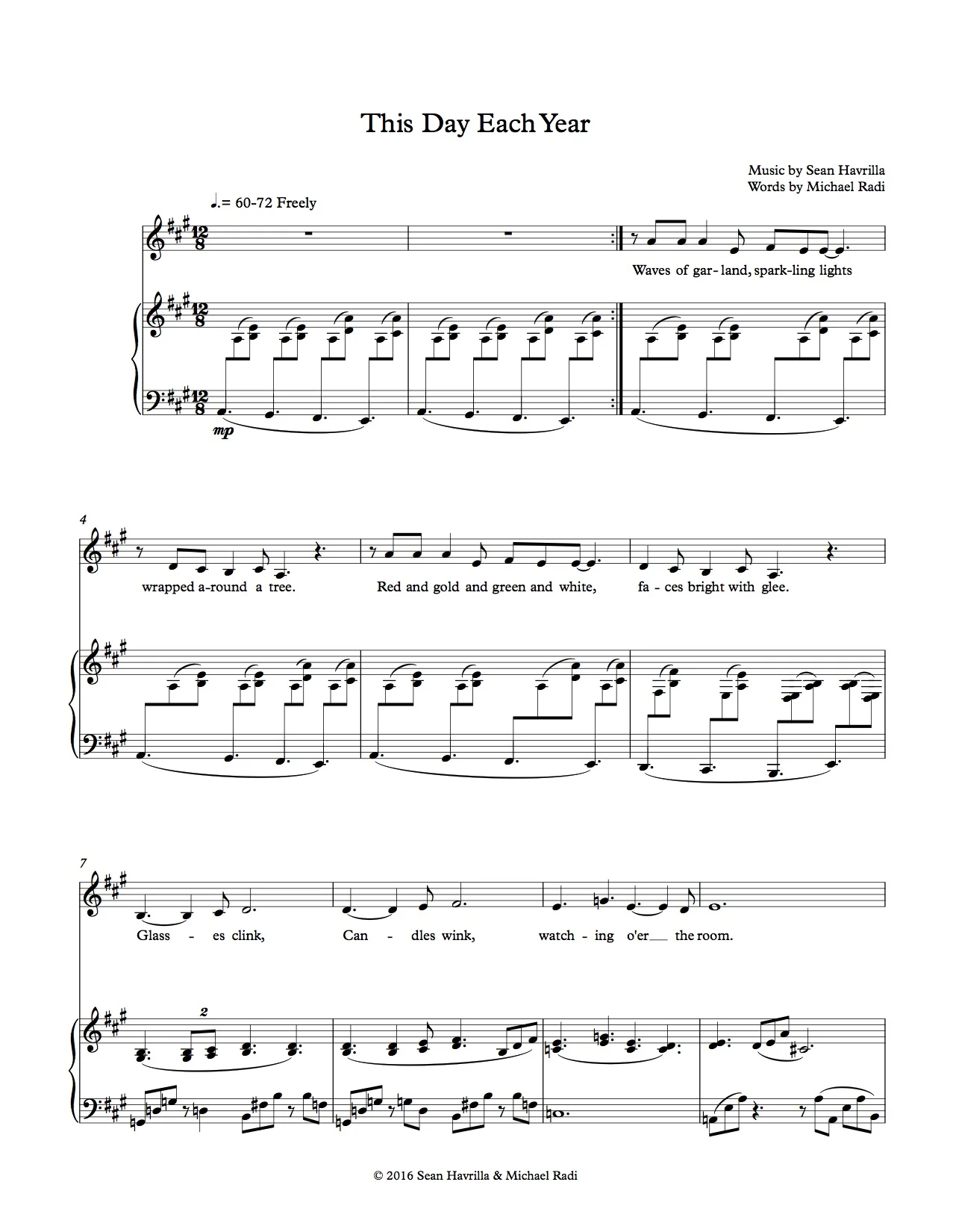

Once we realized that the story, and therefore the entire musical, was about telling stories in order to manipulate and acquire, the music was a natural addition. Add on top that superstition, ghost stories, and the other-worldly lend themselves to musicality as well, and having moments of song became absolutely integral to the storytelling.

All of our main characters needed strong desires. The original story gave very little, particularly to the almost non-existent Katrina Van Tassel, the two-dimensional Brom Bones, and amorphous Baltus Van Tassel, so we provided the extra layers. We came up with what exactly each character desires most and what makes them tick. From there, the question became how exactly would they go about attempting to manipulate their situations and the people around them in order to get their desires. And this is where music came in.

Surprisingly, we discovered that since almost every line and moment of interaction had to do with manipulation, storytelling, and/or the supernatural, moments without music felt extremely odd. Not that we think the show should be sung-through, but underscore became as necessary and enhancing as the song moments. It was a wonderful discovery. The music helps complete this story in the same way that the verbosely descriptive language aided Irving’s original story.

I’m No Expert

I will very readily admit that I am no expert on the topic of musical theatre adaptation, and I am certainly continuing to learn as I go through the process myself. But these are my observations thus far in my career, and I do think they have merit and factual evidence to support them.

Adaptation is hard. But it’s very doable. Without it, most of the musical theatre canon would not exist.

***Another Note: If you’re interested in learning more about my adaptation of The Legend of Sleepy Hollow with composer Sean Havrilla, click on the Musicals page or feel free to contact me!

Otherwise, thank you for reading and happy adapting, my friends!